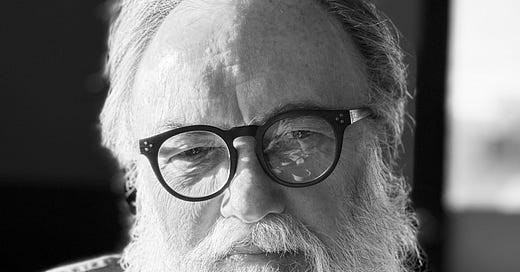

Two weeks ago, on April 18th, 2023, my father Michael T. McCloskey passed away without warning. He was 64, and as far as everyone was aware, he was in good health. I had seen him 2 days earlier. It was a typical visit, and although he was in a hurry that day, his laugh was easy and playful, and his long white beard supported the characteristic gleam of love in his eyes. His embrace was strong and steady when he told me that he loved me before walking out of my house. There was nothing to prepare me for the news of his death: no illness, no accident, no expectation, nor concern over its potential immediacy. It’s been 2 weeks since my mom called and through screams and tears wrenched the words out of her mouth. “Dad passed away.”

The reality of those words - the reality of his absence - still lacks the power to compel my belief. Mark Twain, writing about the death of his daughter, had this to say of his shock (the rest of this passage appears in my eulogy):

It is one of the mysteries of our nature that a man, all unprepared, can receive a thunder-stroke like that and live. There is but one reasonable explanation of it. The intellect is stunned by the shock and but gropingly gathers the meaning of the words. The power to realize their full import is mercifully wanting. The mind has a dumb sense of vast loss that is all. It will take mind and memory months, and possibly years, to gather together the details and thus learn and know the whole extent of the loss.

“Mercifully wanting.” - a tragedy in two words.

On the morning of his memorial service, I struggled to get out of bed. I was reeling from my own thunder-stroke, and it felt like getting up and putting my feet on the floor would make me complicit in this reality that I desperately want not to be real.

But life exists, whether you choose to live it.

Truth exists, whether you choose to believe it.

As I laid there, thinking about the speech I had planned to give at his service, I tried to imagine the words coming out of my mouth, and it felt like a physical impossibility. How could these be true words? How can this be a true moment? Speech has the power to create, acknowledge, legitimize. I didn’t want to lend my tongue to this horrible thing.

I imagined my father - bright, measured, playful, and deeply loving - and I realized that it wasn’t my belief that was being asked of me by life, but my participation. We wake up and the day seems to say, “I hold suffering, but also joy. I hold sadness, but also love. I hold wounding truth, but also tenderness and forgiveness. Do you want to participate?” It seemed to me that my father had always said “Yes!” to this question.

During the several preceding days I had been painfully full of thought, and blindly writing things down as they appeared in my head. My dad had a way of planting time bombs inside of me. Throughout my life he would do or say something, or love in some particular way that I couldn’t understand, or didn’t even see. Sometime later, sometimes years, the bomb would go off, and the landscape of life and love inside of me would be irrevocably altered. Now, thousands of these bombs were going off all at once. I didn’t want to see, and I didn’t want to speak, but I felt strongly that I had something to say - even if I refused to say it.

So I planted my feet, stood on that shaky ground, and said to this day, “Yes, I want to participate.”

The following is what I read to the many friends and family members who gathered to honor my father on April 29th, 2023.

Eulogy for my father

To those who loved my father,

When my son was born I became sharply aware of the relationships in my life, and the role that love played in them. I also became sharply aware that one day I would lose my father. I’ve been afraid of this day for a very long time. It seems to me like something that doesn’t happen at any certain point in time, only something which has a before, and an after. This is a speech I never wanted to give. I’m angry that I have to give it, and yet thankful that I get to. As I began to consider what I might possibly want to say at this moment, what drew heavy on my heart is that I want to talk to you. You who are here now, gathered. I want to talk to you not about what has been lost, but about what is present. Not about memories, but about this living moment. I want to speak to you about what I see as the gift that my father gave the world, and the reason, it seems to me, that we gather here tonight. I want to talk to you about goodness, truth, and relationship. Because that is what he taught me.

My father was a good man. That word ‘good’ is important, and carefully chosen. I want you to consider the depth of it, I suspect it has no bottom. I could have said he was a great man, and while that would be true, it would be to say less, not more. In the beginning when God spoke, and brought into existence the multitudes of being, he looked and saw that it was good. When Susan and Lucy were told about Aslan, they asked “is he safe?” and Mr. Beaver replied, “’Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good.” Consider that you cannot replace the word good with any other synonym in those two instances without draining all of their power. In the heart of greatness is something to be admired. In the heart of goodness is something to be received.

Much like Aslan, your thoughts were not safe around my father. If you spoke to him, something in you would be revealed, brought forward, refined, loved. And it was good. It was good because it was true. Jordan Peterson said “Truth is the handmaiden of love [and] Dialogue is the pathway to truth.” My father told the truth, courageously, and in service of love. And it was good.

I think we naively regard truth as something like a set of facts, which one can simply observe. I don’t think that’s right. I think truth is more like an action than a fact, it’s more like a story - not just something to be known or learned, but something to be played out. It isn’t something which is, but something that happens. If at some point a truth seems tidy like a known or a fact, that is only because we’re at some point in the story from which we can see something clearly. But the story will continue, and we will see differently, and so we must treat the truth reverently, and with humility.

We wake up into consciousness, into this world, into this day, into this story, and respond to what calls. It’s the truth that calls on us, through a friend, through a lover, through a father. The truth is relational like that. It’s not objective. It has to be acted out, to be responded to. And to play that part, to wake up, and to respond, requires humility and courage, both of which my father carried fearfully and strongly. And that story, the story of the truth that my father told with his life, continues. In some sense he is no longer with us. But no light has been turned off, only some change in the structure of life has occurred.

What is this change?

Mark Twain had this to say after the death of his daughter.

“A man's house burns down. The smoking wreckage represents only a ruined home that was dear through years of use and pleasant associations. By and by, as the days and weeks go on, first he misses this, then that, then the other thing. And when he casts about for it he finds that it was in that house. Always it is an essential, there was but one of its kind. It cannot be replaced. It was in that house. It is irrevocably lost. He did not realize that it was an essential when he had it; he only discovers it now when he finds himself balked, hampered, by its absence. It will be years before the tale of lost essentials is complete, and not till then can he truly know the magnitude of the disaster.”

Twain’s house is a powerful analogy, but I don’t think it goes far enough. It isn’t simply essentials that were in that house of my father, but an actual part of me.

Some seem to believe, or at least behave, as though all of who we are is contained within us, within our bodies, or our minds, perhaps our souls. We cherish this idea because it allows us to retreat into ourselves, as if that’s some kind of protection. But this is not the case. Part of you quite literally exists within every person you have ever loved, if you have loved well. If there is a spark of divinity within each one of us, which to me seems undeniable, that spark contains something like omnipresence on a local scale. Just as who you are is distributed across time, and you cannot say of an old man that he is the same man as when he was a young man, you are also distributed across a collection of people who have looked at you, inside you, and received you. You might say that you don’t truly know a man if you don’t know his wife, or children, or his best friends. Everyone that knows you, knows you uniquely, and if I wish to know you, I must know those who you love. My father made my friends his friends, and my friends know me better for it.

We are too big to be known fully to one another, or even to ourselves. Being itself is a communal affair. Being itself is relational, not individual, and not isolated. I know this to be the case, because there is a part of me that I could only access when I talked to my dad. It wasn’t just that he knew something that I needed. There is quite literally a part of me in him. All relationships that are based on love are like this. Some part of you lives in another person. It isn’t just an essential, or something you need, it is quite literally you. In that way Mark Twains analogy seems even more devastating. How can I continue on, with part of me now gone? I can, because strangely I am not less whole. I feel profound loss, but I do not feel diminished, because this coresidence of heart is not just one-way. Just as part of me lived in my father, some unique part of him, lives in me, as it does in everyone here who knew him.

In a way I feel like the luckiest person here. He was my father, he taught me, he molded me with his love since my first day. But a part of me is jealous of the ways that other people knew him. As friend, counselor, brother, husband. That is why we gather. We want to know the part of him that the other carries. I want to know the part of him that you carry with you. We are here not only to celebrate his memory, or to grieve and to mourn, but to partake in his spirit, which each of us carries, in ways that we know, and also in ways that are hidden to us. We are here to witness the pieces of a man that live inside each of us. These are not mere memories. This is presence. It is very real life. So partake of my living father through each other.

Talk to each other, hug, drink, eat, look into each other’s eyes, and know that you are looking at some part of my father. Begin to tell the tale of lost essentials. But again I must disagree with Mr Twain: there is no amount of time adequate enough to complete that tale. The only completeness is outside of time, in Heaven.

My father was a licensed professional counselor. He died laying on his therapeutic couch, during a phone session. There was no struggle or sign of distress. He simply stopped responding in the middle of his conversation with his client. While the shock demands my anger, and my argument with fairness, I rejoice in his health, life, and the love that he shared, all the way up to the moment he left.

I love you Dad.

Oh Matt, I'm so sorry to hear this. I hate that you had to write it, but love how well you honored your father.

So glad to have this in writing, Matt. What a beautiful tribute and a profound way to express how your dad changed everyone around him, everyone he met, and we were so lucky have had him while we did.